- Home

- EN

- Our impact

- ProspeKtive

- When the waiting room shapes our impressions

When the waiting room shapes our impressions

November 2025

The experts

The waiting room is often perceived as a simple place of transit, almost mundane. However, it plays a much more important role than it seems: it influences patients' state of mind, their stress levels, and even their perception of the quality of care and the establishment. Research in management science and psychology has long shown that the physical environment shapes our feelings (Bitner, 1992). The waiting room, the first concrete contact with the medical world, is no exception to this rule (DCunha et al., 2021). Lighting, comfort, seating arrangement, ambient noise... all these details, when taken together, create a unique experience. It is this often underestimated role that we wanted to focus on. To do so, we conducted two successive studies—one qualitative, the other quantitative—which shed additional light on how the layout of a space influences the patient experience.

We first conducted an exploratory qualitative study through two focus groups: one with oncology patients, the other with people without any particular medical history. The aim was to understand how each person perceives the waiting room: what reassures them, what disturbs them, and what makes an impression on them. Three main lessons emerged. First, the waiting room acts as a signal, giving a first impression of the quality of the interaction to come, the professionalism of the doctor, and the welcome offered by the establishment. Second, as mentioned in the literature (Bitner, 1992), certain criteria are considered essential for creating a positive environment: smell, temperature, lighting, cleanliness and comfort of furniture, decoration, music, clear signage, and practical equipment. Finally, participants recognize that the waiting room can encourage interaction between patients, but only if this remains a choice. In summary, two dimensions emerge: the waiting room as a signal of friendliness and competence, and its potential role as a space for interaction. These two points guided the design of the quantitative phase.

The second study was conducted online with 111 participants (average age 40, 64 women, 45 men, 2 non-binary, 81% university graduates) to test, on a larger scale, the impact of seating arrangements on the patient experience and satisfaction. Participants were presented with two scenarios: they had to imagine a first visit to the doctor in a waiting room described as either interactive (chairs close together and facing each other, encouraging conversation) or non-interactive (chairs spaced apart and facing outward, promoting privacy). For this second stage, we focused on two key dimensions: warmth (experienced, for example, through friendliness) and competence, both derived from the Stereotype Content Model (Fiske et al., 2002). These dimensions emerged strongly in our first study and are regularly highlighted in research on the influence of physical spaces (Liu et al., 2018).

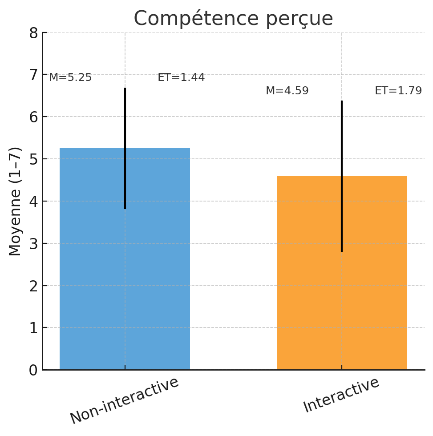

The results show interesting contrasts: interactive rooms are judged to be warmer, but non-interactive rooms appear more competent and, ultimately, generate greater satisfaction. In the following, the results are presented with the mean (M) and standard deviation (SD) in order to reflect both the overall level and the dispersion of responses. In terms of perceived warmth, the interactive room has a clear advantage (M = 4.72; SD = 1.65) compared to the non-interactive room (M = 3.72; SD = 1.80). Participants describe the atmosphere as more friendly and welcoming when the space encourages interaction. For competence, the opposite is true: the non-interactive room is rated more positively (M = 5.25; SD = 1.44) than the interactive room (M = 4.59; SD = 1.79). The sober and distant layout therefore seems to send a signal of seriousness and professionalism. Finally, overall satisfaction is also higher for the non-interactive room (M = 5.20; SD = 1.62) than for the interactive room (M = 4.37; SD = 1.77). Privacy and calm seem to carry more weight than conviviality when it comes to projecting oneself into a medical context.

Averages (M) and standard deviations (SD) for perceived warmth, perceived competence, and overall satisfaction according to waiting room layout (interactive vs. non-interactive room).

But the story doesn't end there. Qualitative interviews had already suggested that patients' personalities played a role in their desire—or lack thereof—to interact in the waiting room. We therefore incorporated this dimension into the quantitative study by measuring extraversion (McCrae & Costa, 1999). The results are clear: more extroverted individuals appreciate interactive rooms more ("Talking to your neighbor in the waiting room can also be good for you, it can be good for the patient; Not being alone like that depends on each person's personality“), while the more introverted feel less comfortable there (”I can't stand being in a waiting room with people I don't know and feeling like I'm being watched"). The same space can therefore elicit opposite reactions depending on the individual. There is therefore no universal “ideal” configuration: it all depends on the type of patient and their needs, which argues for more flexible and adaptive designs.

Overall, these results highlight the importance of design choices, even in spaces that are often considered secondary. A waiting room is not just a backdrop: it sends a strong signal that can inspire confidence, warmth, or competence—but rarely all at once. It can also become a place for interaction, provided that this remains optional, as not all patients have the same desire to interact. There is therefore no universal ideal configuration. The real challenge lies in the ability to find a subtle balance, to offer more flexible and adaptive waiting rooms that can respond to a diversity of profiles and needs.

References

Bitner, M. J. (1992). Servicescapes: The impact of physical surroundings on customers and employees. Journal of marketing, 56(2), 57-71.

DCunha, S., Suresh, S., & Kumar, V. (2021). Service quality in healthcare: Exploring servicescape and patients' perceptions. International Journal of Healthcare Management.

Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J. C., Glick, P., & Xu, J. (2002). A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(6), 878–902.

Liu, S. Q., Bogicevic, V., & Mattila, A. S. (2018). Circular vs. angular servicescape: “Shaping” customer response to a fast service encounter pace. Journal of Business Research, 89, 47-56.

McCrae, R. R., & Costa Jr, P. T. (1999). A five-factor theory of personality. Handbook of personality: Theory and research, 2(1999), 139-153.

Release date: November 2025