- Home

- EN

- Our impact

- ProspeKtive

- Life after lockdown: why go back to the office?

Life after lockdown: why go back to the office?

September 2020

Expert

Should we go back to work at the office? The answers to this question differ depending on whether the respondent belongs to the group of those who have been impatiently awaiting a return to normal, those who have discovered telework and have come to terms with it, or those who remain staunch opponents of it.

Everyone has lived the experience of deconfinement differently and their opinion on the issue depends on objective parameters (manager or not, accommodation suitable for teleworking or not, etc.) and subjective (social, cognitive, emotional or even mental dimensions). There are those who had already practiced, those who ultimately prefer to be in a group rather than alone… the variations are endless. Two main themes emerge, however: the place of the individual within the collective and the organization of work.

ANACT (The French National Agency for the Improvement of Working Conditions) identifies two registers in the implementation of teleworking.

The first is social. Teleworking is seen as a way to improve employee well-being. It facilitates the articulation between professional and private life and promotes access to employment for certain populations (for example, employees in return for parental leave). The modalities of its implementation may vary according to the particular needs of individuals. Teleworking is then a time planning tool and is often practiced on a fixed day in the week.

The second register is organizational. The deployment of teleworking is part of a larger project aimed at changing management practices towards management by objectives. Teleworking therefore potentially applies to everyone as part of a shared approach. It is no longer linked to personal circumstances, but to the tasks to be accomplished and the level of autonomy of employees or their function. Teleworking days are then more numerous (two or three per week, on average) and spread flexibly over the week (or month) depending on the activity. Improving the quality of life at work is thought of in a broader context and encompasses travel time, but also relationships between individuals.

When employees talk about their return to the office, they oscillate between these two registers. What will going back to the office do for them on a personal basis? Is the organization of work going to be changed? When we work at home, it is the requests that are perceived as an intrusion into private life; when we work in the office, it is the commuting time that is seen as an impairment of the quality of life. The individualization of work (management by objectives and talent management, for example) changes the relationship between the company and the individual who would like to be able to negotiate a contract on the basis: "I come if it brings me something. How will going to the office contribute to my personal development or to my individual goals? (The stereotype of this ideal contract is often that of the nomadic worker, who constantly travels and works all over the world thanks to his computer and Internet access.)

Before confinement, telecommuting was usually one to two days a week at home, the rest of the time at the office; now the reverse would be desired. For managers, whatever the individual considerations, it is about avoiding dissolving the collective by reserving for the office the tasks that are best performed there and that create proximity. Studies have shown that it is the sharing of information between individuals and teams, the transmission of knowledge and all events that contribute to the creation of a common identity. Companies that have chosen to no longer have offices keep and value these shared moments.

Thus, the American company Basecamp (digital tools for the organization of remote work) has (almost) no more offices since 2010 and is a textbook case for two reasons. First of all, because of its operation, which has evolved in Remote by David Heinemeier and Jason Fried: when it starts up, the company rents premises. But noting their low use, she gradually reduces them until they are abandoned almost everywhere. Only Chicago-based employees still have offices that also serve as showrooms and host external and internal events. To maintain the link between employees despite the distance that separates them, Basecamp takes great care in its recruitments and makes sure to hire as much as possible talents who share a common passion. She also uses, of course, her work organization solution and has set up specific managerial rituals. Finally, several times a year, she dedicates part of the money not spent on rent to the organization of seminars where all come together and get together.

A first good reason to come back to the office would therefore be to find a meeting place for the clan, a base camp for the tribe. Studies on virtual teams show that, beyond discussion and trust, it is shared identity that best unites members of the same collective. Clearly, the office fosters belonging by materializing and supporting a shared passion.

The myth of the garage (HP, Facebook, Amazon) is used by many companies to create proximity between the collective's mission and individuals. On a much larger scale, BMW's research center in Munich is set up so that engineers can view prototypes of vehicles under development from their workstations.

In the premises of Rémy Cointreau, in Paris, a tailor-made bar has been installed in the employees' relaxation area. Boeing, for its part, developed the Factory-Office Hybrid concept: in Renton, near Seattle, the offices surround the two final assembly lines; the 1,200 salespeople and engineers can thus follow the work of the 900 workers. The link between the two worlds, tertiary and industrial, is reinforced by particularly immersive design codes.

The effect can also be mobilized in services. The audit firm PWC has thus created an Experience Center in Paris where the reception areas for clients and the workspaces of employees are intertwined in crossed paths.

These examples highlight the importance of context in architectural design.

These desks are inspiring not because they are "just like home" or because they have special attention on any hot topic. Some are dense, others flex-office; some have a sophisticated design, others a very simple layout. But all of them are stimulating because they are connected to their purpose.

These offices are the company's embassies to employees and the ecosystem. At a time when teleworking is widespread and the question of returning to the office arises, this symbolism is essential. It gives meaning and becomes a unifying element. The post-crisis office should integrate this dimension from the earliest stages of its design. In addition to creating envy by uniting around common interests, it must take into account the activities that take place there and the motivations that drive employees.

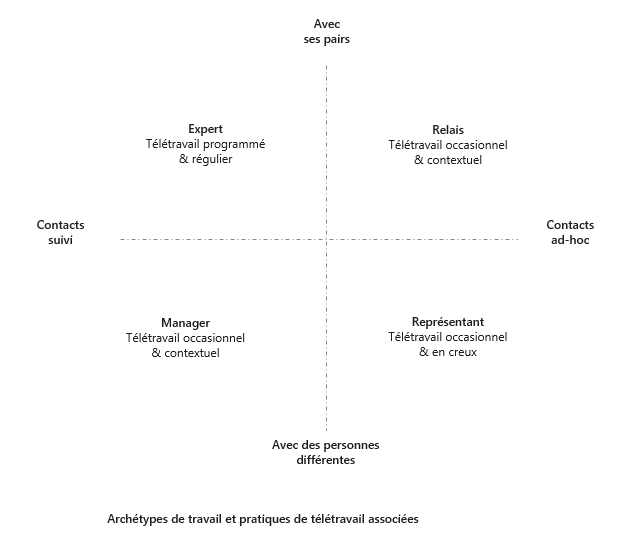

We can divide the employees into four archetypes, each with their motivations and skills, missions and know-how: the specialist (or expert), the relay (or conductor), the representative (or nomad) and finally the manager (or work organizer). Contrary to tradition, the archetype manager is not, here, hierarchically above the others. The manager is simply the one who has the greatest capacity to think and organize work; the specialist is the one who has the greatest knowledge in a given field; the relay is a generalist who knows how to make the link between specialists and move them together towards the goal; the representative values the work of his colleagues, especially outside. Each group has its own expectations in terms of working methods and places: the expert will tend to seek the company of his peers with whom he will deepen his knowledge, the intermediary will interact a lot and will travel frequently in the premises, the manager will work with one or more teams, and the (nomadic) representative will try to connect with as many people as possible when he is passing through.

Teleworking methods can also be associated with each archetype. Rather, the specialist will do continuous teleworking days, regular and scheduled. The relay will prefer to come to the office and will telework occasionally, according to personal constraints or to carry out specific and momentary tasks. The manager will be keen to maintain the link, he will tend to work in the office and telework according to others or, like the relay, to meet specific needs. Finally, the representative will use telework to optimize his schedule: he will therefore be able to work at home, but also in coworking spaces or other company sites located near his home.

To be attractive, the office must therefore allow everyone to fulfill their mission.

and to work according to the typical rhythm of his archetype: number of days per week (or months) of work in the office and succession of tasks when there. The feedback on operations based on mobility is positive when the individual finds it a personal advantage. In order for them to be, we believe in the concept of dens (or clan refuges), multipurpose places from which one can escape, to isolate or regroup, when the need arises. This is a logic of spaces served and spaces used which must be carefully sized, integrated into a tangle of scales, and meet three needs: diversity of uses, optimization of use, and fluidification of flows. The teleworking imposed by the crisis will have shed light on individual logics of work organization. They mark the importance of belonging through common interest and the specificities between four archetypes of workers.

Finally, they allow us to identify two major reasons for going to work in the office: because the place is attractive and immersive; because it stimulates cohesion by grouping people together in multi-use spaces forming part of an ecosystem of spaces.

Release date: September 2020